| Home | The Band | The Music | The Critics & Fans | Other Stuff |

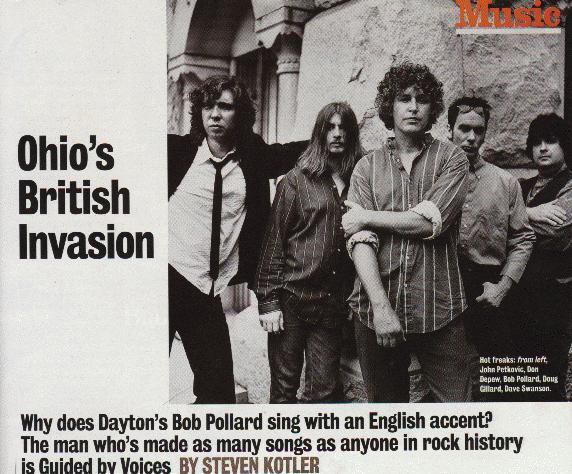

GQ Magazine December 1997 - Photos by Mark Hauser

This is a story that starts with a drink. It is supposed to start with a drink; I mean this is rock and roll and that's what's supposed to happen. But then it happens, and it happens, and it keeps on happening until it's some kind of perpetual-motion machine with a will of its own. In the end, it's a slaughter of Budweiser. In the end, we're rebel drunk in a parking lot, sitting in a car with our feet on the upholstery, howling along with a song on the radio. It happens that I am singing with a man named Bob Pollard in a town called Dayton, Ohio to a song called "Hot Freaks" by a band called Guided By Voices, and despite the fact that there are people out there, I mean multiple thousands who would kill for this experience, it's a very good bet that all of this escapes you.

"Hot Freaks"? Sure, some college radio stations play it, but it's safe to assume that you have never heard "Hot Freaks", never been moved by the guitar-stomping opening or the sly British twist to the vocals or the fleeting logic of the lyrics. The sound is fluid and open, as if you'd poured the Beatles and Beefheart and Big Star down a deep well and left them to age and turn and play all the possibilities, and the sound drifted upward, out of the flat earth, as an assembly so close to everything you've ever heard, ever liked, but not or not quite. It's also safe to assume that most of you have never heard of Bob Pollard or the band he fronts, Guided By Voices. These are safe guesses, but what makes them interesting guesses is that Guided By Voices has been a force in rock and roll for almost two decades and that is has released as many records as any band you can think of and that this output totals close to 400 songs. That is possibly the most songs released by any band ever in the history of rock and roll.

This all happened quietly but inevitably. During GBV's first decade, Pollard taught grade school. GBV recorded in basements - the printings tiny, the songs short, the sound less than radio-friendly. It was a time when no one took GBV seriously. Hell, the band didn't take itself seriously. But slowly the sound got out. People heard; people listened. Enough people listened that the band eventually got signed by Matador. Pollard quit teaching school, and the band changed members. Now, finally, GBV's latest album, Mag Earwhig!, has received some long deserved attention. And so you might say that Bob Pollard, at age 40, has become the oldest rising star in the history of rock and roll.

Pollard credits the GBV fans, who must be amongst the most ardent in rock. On its last tour, GBV made the rounds with Superconductor, a sensation in its own right, and Superconductor was so amazed by GBV's fans that the band's members asked for the secret.

"It's all in the chant," Pollard told them. Aha, the chant. See, GBV fans know to scream "G-B-V!" before the show, to raise their voices in raucous chorus, to shake the very rafters of this, their church. They’re so great, these fans, that Pollard will hoist his beer in holy salute, and he will do so all night long. If you ask him about his drinking, he'll say, "I've been drinking this way since I was 11. I drank when I played basketball, when I taught school, when I played music - I'm all pro."

Drinking is as enmeshed in Pollard's life as Dayton, Ohio is. This is the town that produced the Wright brothers and nearly a hundred years later is still basking in their glory. Dayton is where Pollard grew up, where he met and married his childhood sweetheart, where they had two kids and where he built the Monument Club. The Monument Club is clearly important to Pollard, and it's located, conveniently, in his backyard; in fact, to the untrained eye the club looks like a converted garage. It's a square box of a room with a wet bar, a big-screen TV and an assortment of '60s psychedelic posters for bands like Moby Grape and Big Brother & the Holding Company. This is where Pollard and all his friends get together every Sunday and Wednesday to drink and drink and drink, and it is clear that if the Monument Club is a monument to anything, it is to drinking and to friendship, to the kind of drinking and friendship it takes a lifetime in a place like Dayton, Ohio, to produce.

Behind the club is another monument, a miniature basketball court made of sun-baked, cracked concrete. It's there because Pollard comes from a family of jocks. He was a jock; his brother was a jock; his father was a jock. His father was so much of a jock that when pollard began to get into music; when he began to veer from the path of jockness, his father tried to keep him and his brother separated, tried to diminish the possibility of rock and roll rubbing off on his other son.

Bob Pollard has a near encyclopedic catalog of music in his head. In conversation he jumps from Jimmy Web to Unsane to the Beatles, and to him they are all part of the same discussion - they are rock and roll - and fundamentally, that is the only discussion Pollard knows how to have. It is so important that when he sits on the toilet he sings out his toilet trilogy; a medley of Mott The Hopple, Styx and Queen. He breaks into song a lot, in public and in private; he does it for the pure joy of the music. We are in a bar as he speaks of Led Zeppelin, and he cannot merely speak. Forget the patrons; he must sing "No Quarter" for me. He must sing the lyrics and the drums and the vagrant guitar whine and the eight-octave changes, and he must do it in a British accent.

The accent is something he has down. Bob Pollard is from Dayton, Ohio, and he sings with a British accent. He doesn't do this because he is pretentious; he doesn't do this because he is a veiled expatriate; he does this because that is how he hears his songs. When he was growing up, he was obsessed with the British invasion, and much of the invasion came complete with accents. Over the years, Pollard has taken a lot of shit about the accent, but remember that what gave Mick Jagger that twangy morass of a voice was his attempt to sound blue, to sound like an old, poor black man from the Deep South, to sound exactly like Robert Johnson once sounded. If you ask Pollard why he became a musician, he'll tell you that "there comes a time when you don't hear the music you want to hear, when it doesn't exists, so you have to go out and make it yourself." So Pollard sounds English or almost English or a little like very early David Bowie, a little like Bowie when he released a painfully obscure album called Love You Till Tuesday. Pollard, of course, has heard of Love You Till Tuesday and can not only tell you who played drums on it and who produced it but also list all the songs and sing all the words. He can do this because these are the voices in his head; these are the things that guide him.

The lyrical landscape of GBV is both alien and familiar. The words have become legend to GBV followers, and they do what all good legends do, they don't make sense. They come from a place of metaphor, of analogy, of come distant hint, so that when taken together they make such perfect sense you want to stand on a table a cry: "She… took me to the new church/ And baptized me with salt/ She told me liquor/ I am a new man." You want to cry these words out, and you will. You'll be drunk, singing along, unable to stop yourself and happily wondering what the hell you are saying. Take the titles of the first four songs on the band's 1994 album Bee Thousand: "Hardcore UFOs", "Buzzards and Dreadful Crows", "Tractor Rape Chain" and "The Goldheart Mountaintop Queen Directory." Now what do they mean? But this lack of direct connotation is part of their genius: They emerge from a place indescribable to take you to another place indescribable, and the whole-blessed experience is hauntingly familiar. They are rock and roll - they are the steps on that stairway to heaven.

As Pollard says, "I feel sorry for a 22-year-old who's trying to be a great musician. He doesn't have the knowledge; he doesn't know the history; he hasn't logged the miles." This is important because there is an unspoken rule in music: Rock musicians cannot grow old, they must stage creaky world tours or appear only on MTV Unplugged. That is the rule, but GBV, just breaking out, is at the forefront of history here. They are old, they are not Spice Girl sexy, and they do not smell like teen spirit.

So Bob Pollard, at 40, and the rest of the over-thirty guys in Guided By Voices are the beginning of the new beginning. They do not wear flannel. They do not have to jump around onstage and kick their legs and practice their Chuck Berry walks or their Roger Daltry microphone spins or their Eddie Vedder slouches, but they do practice these things so they can do them when they feel like it. They do every little thing that comes from the galactic catalog of rock, and they do this because they know, because they've already had their happy ending, because they are what comes next.